Artículo publicado en la revista Archaeoastronomy, publicada por la University of Texas Press, volúmen 22, pps. 131 – 138, Austin, Texas, USA, 2009.

Abstract

At the little-known site of Caballito Blanco, Oaxaca, there is a five-sided structure (Building O) that greatly resembles Building J from. Monte Albán; the latter is famous for its design in the form of an arrowhead; the former, however, has remained almost unknown despite its proximity and easy access. In this article this structure is minutely described, including orientation and characteristics, together with the other cxtant buildings at Caballito Blanco. The area was first studied by John Paddock in 1959 and 1960; no other surveys have been conducted there since.

Resumen

En el sitio llamado Caballito Blanco, Oaxaca, hay un edificio de cinco lados (Edificio 0) muy similar al Edificio J de Monte Albán que es famoso por su forma en punta de flecha; sin embargo, ha permanecido casi desconocido a pesar de su proximidad y acceso fácil. En este articulo, esta estructura se describe en detalle menor, incluyendo la orientación y características, junto con los edificios existentes en Caballito Blanco. La area fue estudiada primera vez por John Paddock en 1959 y 1960; no otros estudios se han realizado allí desde entonces.

Archaeology, Caballito Blanco, Oaxaca, Monte Albán

For Anthony F. Aveni, who opened the way?

In Mesoamerica there are structures whose shapes are something out of the ordinary. This itself has attracted attention, although the shapes don’t necessarily always mean anything in particular. In fact, there may be cases where archaeology has forced some structures to say more than they really mean. In this case, there are two five-sided buildings in Oaxaca where one side of the building is a point, which itself indicates something and must surcly be significant, as we shall see. Exactly what is indicated has been a point of debate that has become a feature in discussion of the two sites, Caballito Blanco and Monte Albán. I want to present here a more detailed study of Building O at Caballito Blanco to facilitate its study by specialists.

Caballito Blanco is a curious case, having been abandoned for half a century despite being on the road to Mitla, on the branch road to Yagul, and in plain view. Although restoration work is now being done (in 2010), there were conflicts that led to its neglect for many years; the lack of detailed documentation is striking.

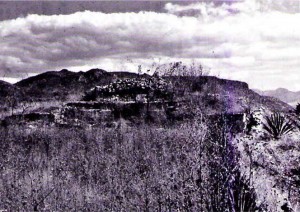

The site is located on a large promontory in front of the town of Tlacolula (Figure 1). The town rises gently behind the site, and the land has been leveled out by gardens. The site is accessed via a path along the cliff itself to get to the plateau. The steps carved in the rock are mostly ‘ancient and very narrow, and they provide a beautiful view of the valley. Before reaching the summit, on a shelf there is a large cross, part of the pilgrimage system in this valley.

On the front face of the plateau a rock drawing can be made out; it is white and pink and possibly in the shape of a dragonfly, which in the region is also known as a caballito blanco (little white horse). In fact, the drawing is so ambiguous that it has been interpreted in a number of ways: «It has a row of Greek frets at the base and suggests the form of an organ or candelabra with five arms» (Bradomín 1978:17). In the upper part there are three visible structures and scattered fragments of others, remains of a possible larger ancient settlement.

One feature of Caballito Blanco that differs from Monte Albán is that it is not fortified and has no complex entrance except for the facade facing the valley. Some walls or retaining walls can be seen that form tenaces for planting, made with stones from the site. In a plot of land adjoining the archaeological structures, there is a modern house made of stones taken from the old buildings. The work carried out for this study consisted only of a detailed examination of everything extant using current technology; no excavation work was done.

The area may have been discovered while work was being done at nearby Yagul ruins where Ignacio Bernal and Lorenzo Gamio (1974) carried out major restoration work and where John Paddock also excavated. But for some reason Bernal and the INAH did not work on Caballito Blanco. Work was done both there and at Lambityeco by Paddock, who had been active since 1954, working for the Mexico City College, like Bernal (Plunket 2003). With the passing of the years and after the publication of Paddock’s classic book (1966), which only offers a few fines and a plan of Building O, comparing it to a similar one at Monte Albán, few authors referred to the site.

Figure 1. View of the Caballito Blanco complex on a large promontory outside the town of Tlacolula, Oaxaca (photo courtesy of A. F. Aveni, 1974)

It is possible that because of Paddock’s sporadic way of working, information on excavation has remained unpublished (1962:165-172). Different plans of the site have perhaps been made without knowledge of other existing plans. There is one very oversimplified plan drawn in 1959 on which the narre of Bruce Leer appears and a subsequent one by Browning and Rattray made for the Universidad de las Américas, most probably at the request of Paddock himself. Evidently, the following year a broader plan was drawn as the excavations progressed, but it was not publishcd, and we have been unable to locate it.

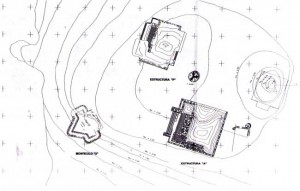

The site, as we know it, consisted of what can be seen in those plans: a central building called 1 -S with an extension called E-1, which today is our Structure A. Slightly to the northwest is the current Structure P, which at the time was called W-1. Around them there were four small mounds and an excavation area that turned up two interments joined to a small teína .cal. At present only our Building O is extant. In 1975 Anthony Aveni published a simplified plan by R. M. Linsley with more accurate astronomical figures than had previously been available (1975:175), and the building carne to be the subject of archaeoastronomical discussions, to be detailed below (Aveni 1977).

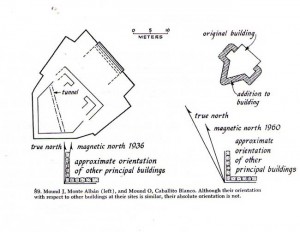

As cited in the work reports, in 1960 archaeological investigations began on Building O, where first the corners were found to be round, and then similarities were observed with Building J at Monte Albán. An initial comparison of Buildings O and J was made by Paddock in his book on the area, showing that although they are similar and have a similar orientation in relation to other buildings, the point they are oriented toward is not exactly the same (1966:89). A study of their orientations was presented by Aveni (1975; Aveni and Linsley 1972) and, more recently, by Damon Peeler and Marcus Winter (2001), who hypothesized on the signifieanee of the distances between the sites in the region.

Caballito Blanco currently only has three structures around a courtyard (Buildings A, P, and E), with visible remains of other structures already quite destroyed and shapeless; the nearby Building O is off-center. The rest are isolated evidence of floors or walls of a few stones or plaster on the ground that rain erosion has removed. The original square must have been extremely flush, as the whole has only a 50-cm difference in height over more than 50 m in length. Building O, in eontrast, is obviously located on a slope on the edge of a possible square. The height of the squarc was increased by almost 2 m to provide crop fields, and so its pointed end looked out over the valley. Might this be one of the many sites that the codices show as a place for observing the skies, represented by a building and an eye inside crossed lines (Hartung 1977)? Might it be one of the sites that marked temporary measurements in spatial distances, as Peeler and Winter (2001) postulated?

Let us consider that although the measurement is not completely determined, from available maps the distance between Mound (Building) J and Building O is 35.5 km, elose to the calendar measurement of 365 it would supposedly have aeeording to theories for the sites in this chronology (Peeler and Winter 2001). There is currently little that we can appreciate in the volumetric and spatial aspect of this group, and we know that what we see is partial because there are various mounds that have disappeared. Evidence suggests that the location, at the highest and farthest pan of the platean, provided those who used it increased security and perhaps greater status or domination because it may have allowed them to have greater control over a broad swath of the territory.

Figure 2. Caballito Blanco Building O showing arrowhead-point corner viewed from the outside (photo courtesy of A. F. Aveni, 1974)

Figure 3. Caballito Blanco Building O showind arrow head point corner viewed from inside the structure (photo courtesy of A. F. Aveni, 1974)

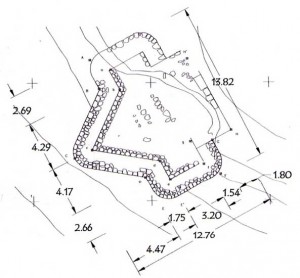

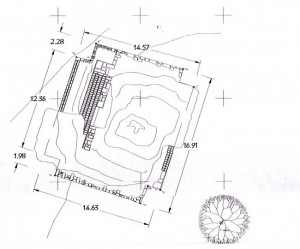

Building O is located almost on the southwestern edge of the plateau. Aceording to previously cited works, it has been possible to chronologically lo-cate this mound, both by the ceramics found in the surrounding areas as well as by radiocarbon dating taken from a deposit of ashes loeated in one of the orners of the structure, in the late seeond period of Monte Albán (Caso 1938), placing it between 100 B.C.E. and 300 C.E., so the date determined as 275 seems about right. It is undoubtedly a site from the Zapotee civilization. The floor is remarkable, as it is very similar to Building J at Monte Albán. This is due to its arrowhead chape, pointing between south and west (see Figures 2 and 3). Similarities between both structures can also be found in the location of the staircase and the existenee of an upper chamber as well as having two main construeted levels.

Some time ago, in following Paddock’s observations regarding the angular similarity between buildings in the two locations, although with a different viewpoint at the narrow end of the building, Aveni started to study the possible orientation toward Capella. The hypothesis was that they functioned at the same time as observatories but with different objectives. In this ease «the phenomenon of the heliacal raising of Capella on the day of the zenith passage [is] the most likely explanation» (Aveni 1975:15). A slightly later study led him to analyze the ease in greater detail and gives Sirius an important role in the orientation, with the object of dividing the year in two near-equal halves. Both in these interpretations and in the orientation of the base or front staircase, as in the ease of Monte Albán, it ean be seen that these buildings played an astronomical role, although it is difficult to understand today what that role was.

As regards their location in the group, it is currently only possible to infer that two definite courtyards or squares existed, one toward Building O, between Mounds A, O, and P, where the stairease of Structure A indicates a functional relation between this and Building O that is emphasized by the superposition, which made it larger. In turn, and given its location at the point of greatest preeminence of the group, it play s the most important spatial role apart from any function it may have had. The seeond courtyard or square is a quadrangular shape and is delimited between Mounds A, P, and El, opens to the north side. It appears to be related direetly to some room that existed to the east of Mound A; it also has a passageway toward the western edge of the plateau via Mound P, which is the only one with two staircases.

The bibliography has established that the line joining the two buildings, in Monte Albán and Caballito Blanco, is 108° (Peeler and Winter 2001), the tip of Mound O points toward 251°, 18″ approximately (Avení 1975:Figure 3). This means that it looks toward the town of Jalieza, a site whose importante in the region has only recently become known and has scarcely been studied to date. Likewise, if we draw a line between this place and Monte Albán, a near right angle is formed, as the angle between the two places is 92°. We will leave the significante of this as an open question. The average altitude aboye sea level is, in the case of Caballito Blanco, 1,649 m and in the case of Monte Albán, 1,913 m. The respective coordinates taken at the tips of each of the buildings are as follows: Caballito Blanco, latitude 16°56’45.3″ N, longitude 96°27’9.8″ W; Monte Albán, latitude 17°2’28.5″ N, longitude 96°46’4.7″ W. The result of this study provides more information on this unusual archaeological evidente and its possible functions.

Bernd Fahmel (1992) has already published an evolution of zenith observation systems in Monte Albán, although with a possible application to the Zapotec region. If Caballito Blanco is contemporary to Building J of Monte Albán (Marcus and Flannery 2001), this reconstruction of the process would be confirmed and would open the doors to a search for other similar structures, perhaps not in form but certainly in function, at the cites that were occupied at the same time. And Caballito Blanco may not have been a site of large dimensions, only a little more than what we find today, but it had a function in the valley that in those times may have established its centralized domination. That is, it may have been an observatory, but it played part of a political role in the redefinition of the Zapotecs’ domination of the region.

Acknowledgments

This study was done as part of postgraduate teaching activity at the Escuela de Arquitectura de la Universidad Regional del Sureste, for the master’s course in restoration of building heritage, 2004-2005; site mapping included the participation of Verónica Arredondo Paulín, Miriam Canseco López, Gustavo Donnadieu Cervantes, Alfonso Espriella, Eduardo Guerra Ogarrio, Gerardo López Nogales, Ernesto López Velasco, and Antonio Melgoza. We are thankful to Nelly Robles García for all her work as well as to the staff at the INAH Regional Center in Oaxaca; the assistance of Anthony Aveni and Bernd Fahmel has been enormous.

Referentes

Aveni, Anthony

1975 Possible Astronomical Orientations in Ancient Mesoamerica. In Archaeoastronomy in PreColumbian America, edited by Anthony F. Aveni, pp. 163-190. University of Texas Press, Austin.

1977 Concepts of Positional Astronomy. In Native American Astronomy, edited by Anthony F. Aveni, pp. 3-19. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Aveni, Anthony, and R. M. Linsley

1972 Mound J, Monte Alban: Possible Astronomical Orientation. American Antiquity 37:528-531. Bernal, Ignacio, and Lorenzo Gamio

1974 Yagul, el palacio de los seis patios. Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas, UNAM, Mexico City.

Bradomín, José María

1978, Historia antigua de Oaxaca. Author’s edition, Oaxaca.

Caso, Alfonso

1938 Exploraciones en Oaxaca, quinta y sexta temporada,1936-37. Instituto Panamericano de Geografía e Historia, Mexico City.

Fahmel, Bernd

1992 El complejo de observación cenital en Monte Albán, historia de una institución. In Homenaje a Alfonso Villa Rojas, pp. 529-545. Consejo Estatal de Fomento a la Investigación y Difusión de la Cultura, Chiapas.

Hartung, Horst

1977 Astronomical Signs in the Codices Bodley and Selden. In Native American Astronomy, edited by Anthony F. Aveni, pp. 37-41. University of Texas Press, Austin.

INEGI

1996 Carta topográfica escala 1:50.000: Tlacolula de Matamoros. Mosaico E14D58. 1996. Mexico City. Marcus, Joyce, and Kent Flannery

200, 1 La civilización zapoteca, como evolucionó la sociedad urbana en el valle de Oaxaca. Fondo de Cultura Económica, Mexico City.

Paddock, John

1962 Reporte de los trabajos de exploración en Caballito Blanco. Biblioteca del INAH—Programa de Conservación de Monte Albán.

1966 Oaxaca in ancient Mesoamerica. In Ancient Oaxaca: Discoveries in Mexican Archeology and Historv, edited by John Paddock, pp. 87-242. Stanford University Press, Stanford, California.

Peeler, Damon E., and Marcus Winter

2001 Tiempo sagrado, espacio sagrado. INAH. Mexico City.

Plunket, Patricia (editor)

2003 Homenaje a John Paddock. Universidad de las Américas, Puebla.

Schávelzon, Daniel

n.d. Caballito Blanco, Oaxaca, un estudio del sitio y de su observatorio. Accepted for publication in Mexicon, Graz.